When we started Segment, we knew nothing about business finance. My background was in aerospace engineering, and my co-founders came from computer science and design. Beyond the hilariously overcomplicated spreadsheet we used to manage grocery bills as roommates, we really had no experience in finance when we started the company.

In the past 2 years Segment has grown from 4 to 60 people, signed up thousands of customers, and raised $44m over a few rounds of financing. Out of necessity we’ve learned the basics of accounting, invoicing & contracts, billing periods, bank account structures, strategic finance and growth models.

But it’s been hard to piece together. Bits and pieces from accountants, lawyers, our CFO and reading a random book or two off Amazon that looked promising. Although startups have developed a culture of sharing learnings, finance generally remains pretty hush hush. Notable exceptions are Everpix’s eye-opening post-mortem, Baremetric’s Open Startups, Mattermark’s complex fundraising tale and oodles of general advice about fundraising. It’s a tricky topic.

This article is part of a two-part series outlining what I’ve learned about startup finance, from a practical perspective. I’ve tried to include diagrams, charts, and redacted docs where helpful.

Part I covers some of our learnings in accounting: accurately recording the past. Accounting is rigorously pedantic to record exactly what’s happened. Then, in Part II I’ll talk about some adventures in strategic finance. Strategic finance is exactly the opposite of accounting. It looks to the future, attempts to guesstimate the fuzzy unknowns, and searches for ways to mitigate risk and increase growth.

Part I: Accounting — Bank Accounts, Credit Cards, Invoices & Contracts

Part II: Strategic Finance — CFOs, Annual Prepayment, Venture Debt & Shadow Budgets

Accounting

I learned the basics of accounting from “Accounting for Developers” and this little book, not to actually do the accounting for ourselves, but to understand what our bookkeeper was taking care of for us. As we grew, problems came up that weren’t covered there, like structuring bank accounts, dealing with lack of credit history, and how contracts and invoicing actually work.

Bank Account Structure

When we were just getting started, we set up a company bank account like any normal person. We opened a checking account. Done!

But then we raised a new round of financing (very exciting), and started to build the team. With $2m in the bank and a payroll to hit, we started to get nervous about that $2m being so easy to access.

Our customer base was growing, and we were giving our bank account number to receive ACH payments from customers… the same bank account that held the entire livelihood of the company in cash! According to warnings from our peers on the ycfounders forum, it’s reasonably common for leaked bank account numbers to get hit with fraudulent withdrawals.

After we raised our Series A and added another $15m to the account, our simplistic checking account structure made us even less comfortable. We needed to be able to spend money easily, but we wanted the majority of the balance set aside securely.

This is when our CFO put in place a new bank account structure.

First, since our new $15m+ balance was way above FDIC insurance limits (the government insures up to $0.25m per entity, per account type, per bank), cash backed by the bank was no longer the safest asset. We moved most of our cash to a money market account invested purely in US treasury bills, which are considered a bit more secure in case the bank collapses or places a temporary hold on funds during a bank run. You may think this is unlikely, but 140 banks failed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and Greece just had a bank run in July. We wanted to be safe.

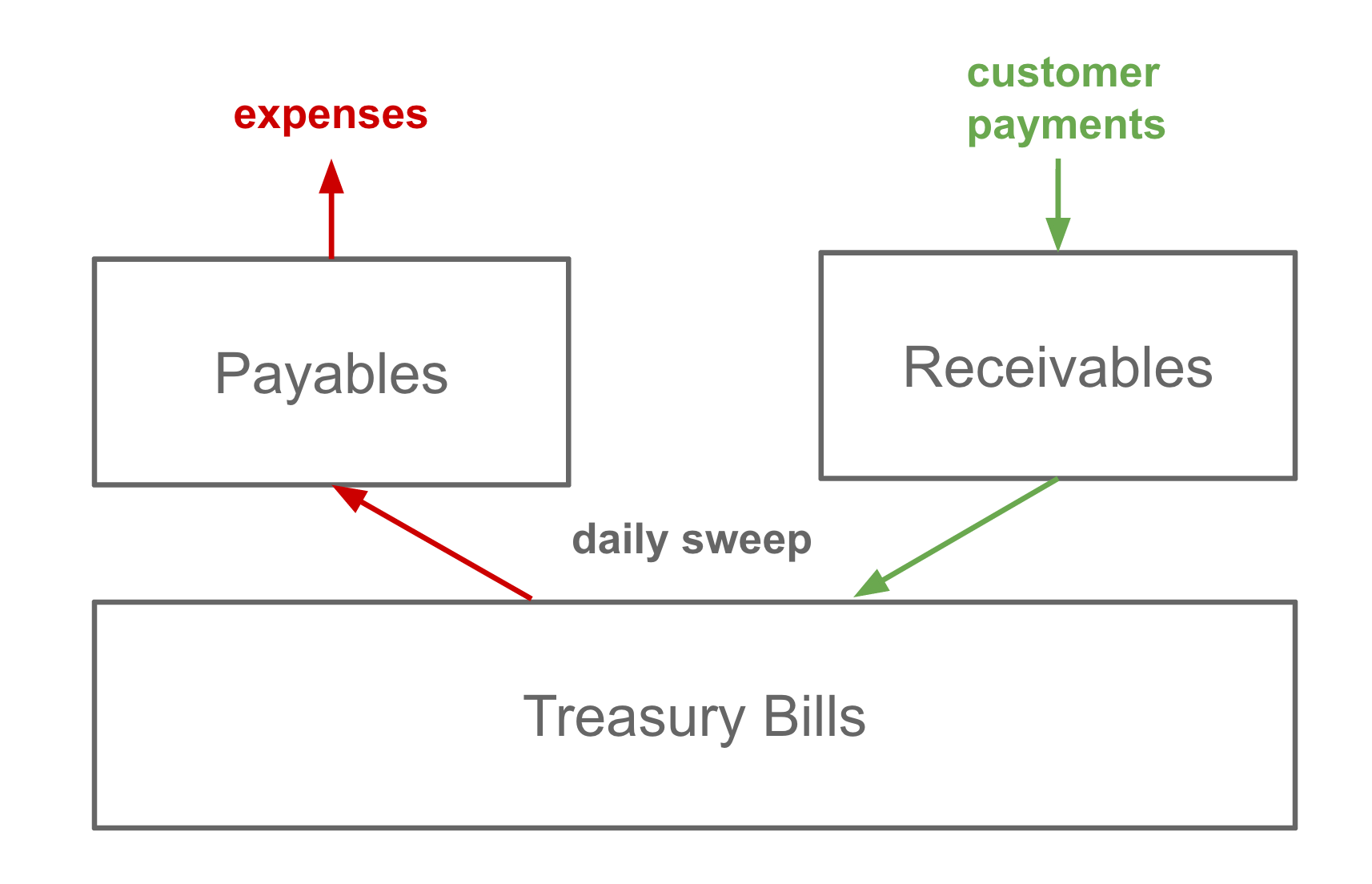

Second, we created a receivables account that can only accept deposits. The bank simply rejects attempted debits to the account. We hand out the receivables account number to customers with abandon, because it only exists as an endpoint for customer payments. It also makes it easy for accounting to see an isolated list of customer payments.

Third, we created a payables account that we keep more private. We maintain a small balance in this account that comfortably covers daily expenses.

Fourth, we asked our bank to set up an automatic “sweep”. At the end of every day it automatically transfers everything from receivables to the treasury bills account, and refills payables.

This account structure simplified our cash management, so that we spend less time running around making internal transfers. Plus, it gives us better security and reduces financial risk. It’s an easy way to sleep better at night.

Credit Cards

Many founders I’ve talked to have struggled with banks giving their startups low credit limits. We’ve also been stonewalled, but hopefully this story gives you some negotiating tips. Initially each founder just had a simple debit card, because that’s what automatically came with our checking account. Wonderful! Then we hit a problem: there are limitations to debit cards (e.g. you can’t rent cars).

So, we switched from debit to credit cards to solve the problem. But alas, credit limits for startups are downright draconian. For example, Silicon Valley Bank credit card requires you to pay the entire credit limit in cash, which they hold on deposit, and then they still charge interest if you’re late on a payment. More than once we had late fees when autopay didn’t work.

We switched to Bank of America after that, but were only allowed a laughably low credit limit:

—February 2014—

BoA: What credit limit are you looking for?

Me: We’ll need at least $20k for our monthly operating expenses.

BoA: Ok, I have a few questions. What was your revenue last year?

Me: Around $40k.

BoA: Got it, what do you expect your revenue to be this year?

Me: Over $2m.

BoA: Uh huh... [suppressed laughter]… ok, um, I’m going to

approve you for a credit limit of $5,000 per month.

Me: [hahaha, what am i supposed to do with that? pay it off

four times a month?]

Every six months or so we had the same predictable conversation with a BoA risk analyst, inching up our credit limit. Ultimately I found we could get more reasonable limits by steering the conversation away from revenue, where high growth startups sound incredibly strange, and focusing instead on our cash balance, which was inflated by fundraising. The line we resorted to (with narrowly suppressed laughter at the absurdity of it) was “We could transfer in a couple million in cash, if it would help?” BoA is not used to dealing with snarky, frustrated startup founders, and the line worked: we got significantly higher credit limits. We were fortunate in being well-funded, and this was a useful moment to flaunt it.

Eventually, Bank of America wasn’t able to keep up with our credit limit needs (when we needed to jump from $75k/mo to $200k/mo). And worryingly for me personally, in a disaster scenario I was personally liable for the card balance in lieu of the company. So, we’ve switched back to SVB to increase our credit limit (which they’ll hold on deposit, sigh).

Contracts and Invoicing

Two years ago we had no idea how selling to other businesses worked at a operational level. None of us had ever done it before, or even worked at a company that had done it before. We started by accepting payments through Stripe, which was nice and simple. But as our customers grew, so too did the size of payments and the need for customized terms of service.

We learned that for software contracts above $20k per year, most companies didn’t expect to put it on a credit card. They expected to be invoiced once, with signed terms of service reviewed by their legal team. So when we started closing our first “business tier” contracts in Fall 2013, we expanded our accepted payment methods beyond Stripe to include paper contracts and invoices.

If you haven’t seen this before, here’s the basics of how it works:

Contracts are usually structured as a Master Services Agreement (MSA) with one or more Order Forms. The master services agreement covers the contractual agreement about liability, confidentiality, payment and termination. The order form is meant to be an easily readable description of what’s being sold and paid in what timeframe, to whom. Here’s an anonymized order form from Segment:

The master services agreement is designed to allow future orders at the same company (e.g. additional teams or departments) to be executed as quick signatures on a new order form, without another legal review process. This makes it easy for a customer to expand their account, no muss no fuss.

We’ve found that the liability terms of the master services agreement are the most hotly contested. No one wants to be on the line if things go south. If you’re selling these kinds of contracts, you’ll likely need to purchase general business liability insurance (and we have extra insurance for data security). From what we’ve seen, insurance for several million in liability seems to start around $10-20k per year. Then, in the contract you hold the line on your maximum liability as the amount you have insured!

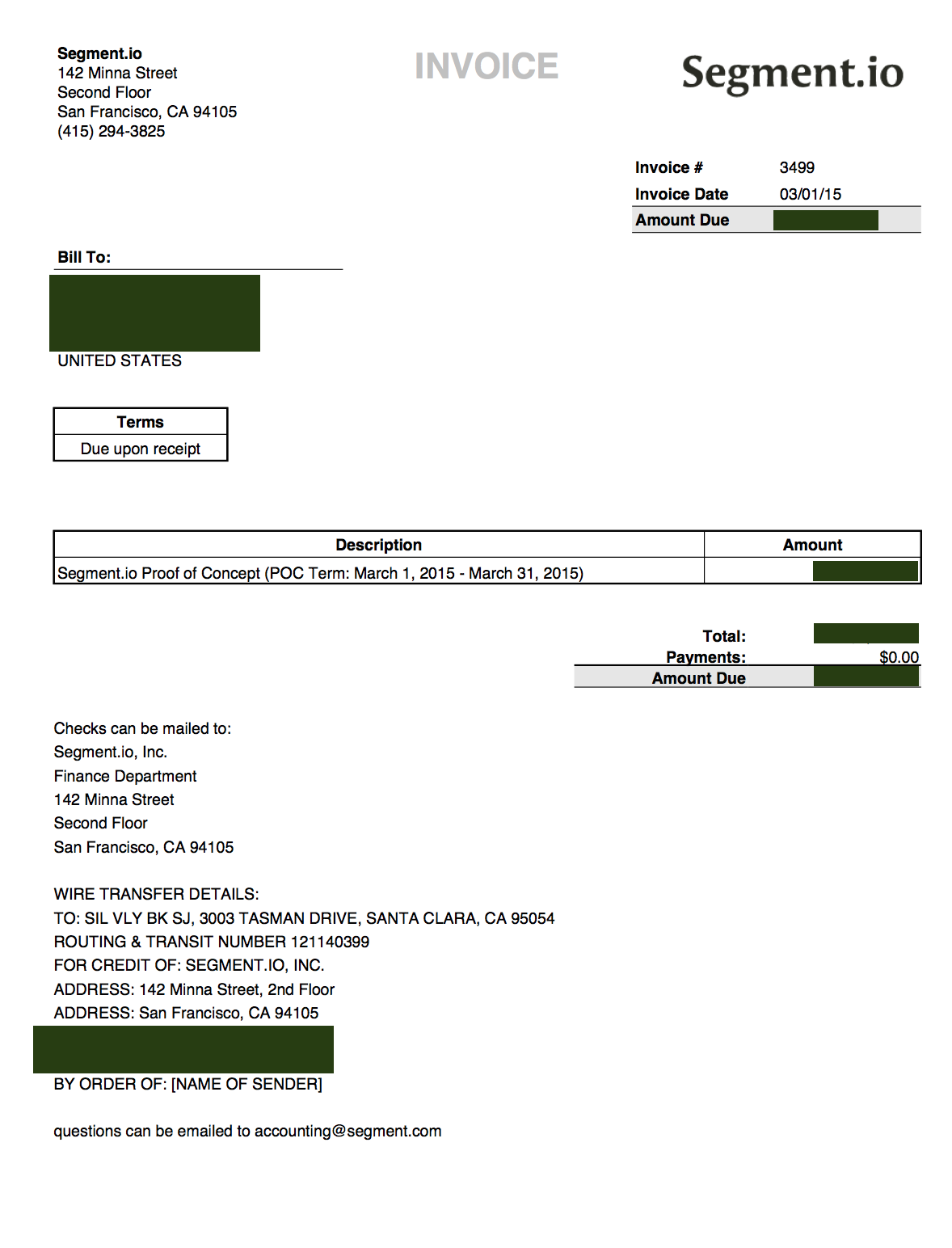

Invoicing was new to us back then as well. Here’s an example invoice, which simply gets sent to the financial contact listed on the order form.This article covers some of the common practices we’ve learned in startup accounting. The next article will cover “strategic finance,” the forward-looking, predictive part of finance in a startup. It should be posted here in a week or two.

If you’re looking for a great way to do bookkeeping, check out Pilot. A number of companies I’ve invested in have used them and found it incredibly helpful and easy.

This article covers some of the common practices we’ve learned in startup accounting. The next article will cover “strategic finance,” the forward-looking, predictive part of finance in a startup.