This is part two of a series outlining practical lessons I’ve learned about finance at Segment. Part I covered accounting. This article covers strategic finance, the exact opposite of accounting. Strategic finance looks to the future, attempts to guesstimate the fuzzy unknowns, and searches for ways to mitigate risk and increase growth.

Strategic Finance

The most dramatic part of strategic finance is fundraising. It’s very exciting to sign your Series Seed/A/B/C term sheet, receive a huge wire transfer, and then see your company splashed across the press headlines. But I won’t discuss fundraising here because others have been over it in great depth. For example, Paul Graham’s essays: How to Raise Money, Investor Herd Dynamics, and How to Convince Investors. Instead, in this article I’ll focus on some untouched practical pieces of strategic finance: when and why we hired a part-time CFO, the importance of annual prepayment, why we decided to avoid venture debt thus far, and how we use a “shadow budget”.

Part-time CFO

When we were getting ready to raise our Series A, we realized we needed more help with finance. It wasn’t easy pulling together all the financial and legal documents for the fundraise, and our bookkeeper wasn’t prepared to help with this level of financial diligence and strategic thinking (how much to raise? why? based on what parameters?). We really needed someone to own finance as a whole, run a tighter accounting process, and advise us on strategic finance issues like insurance, fundraising, venture debt and growth modeling.

We interviewed five part-time CFO firms based in San Francisco, and ultimately hired Jeff Burkland of Burkland Associates. Without knowing much about CFOs, we were looking for someone who was already teaching us things about finance in the interviews, and someone who was a culture fit. It’s been enormously helpful to have senior financial advice, not just for fundraising but also for thinking strategically about sales, marketing spend, and hiring. Most of the learnings below are things we’ve learned from Jeff.

Looking back now, I feel strongly that if you as a founder are spending any time at all on finance (beyond pitching investors during a fundraise), then you should outsource it to a bookkeeper for accounting, or a CFO for accounting and strategic finance. There’s a lot to learn, and without some experienced financial help, seemingly small projects like “get the insurance we need for that sales contract” can balloon into weeks of research, phone calls and silly delays. With a CFO that time sink just evaporates and you go back to working on real bottlenecks in the business. As my co-founder Calvin says: “Would recommend to a friend!”

Annual Prepayment

Two years ago our sales advisor scolded me “You should only ever accept contracts with annual prepayment, it makes a big difference for cash flow.” I thought to myself “yeah, ok, whatever. why not!” So we followed his advice (without understanding it), and just went about our business selling contracts with annual prepayment. But we didn’t really understand what “cash flow” meant, so we started to slip. Pretty soon every contract was billed quarterly or monthly, because it was a bit easier to close deals that way.

Well, it turns out that monthly and quarterly billing was a huge nightmare for our office manager Jenn (we didn’t have an accounting team yet). Invoicing monthly and getting people to actually write checks on time every month is just a massive time sink, for you and your customers.

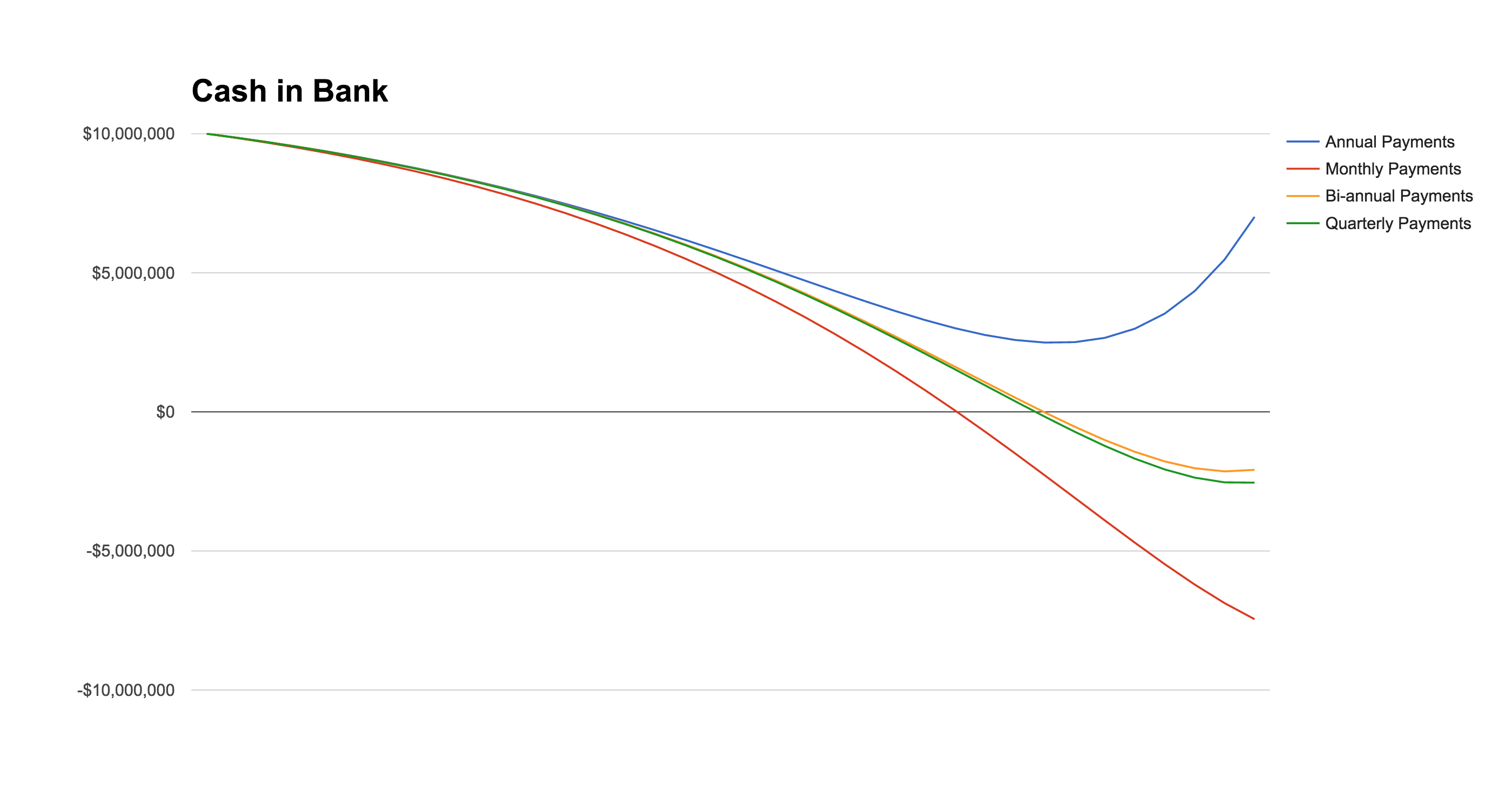

Then one day our CFO Jeff comes to me and says, “hey I want to show you something.” On a single graph he showed me the difference between annual and monthly payments. Here’s a fictional version, showing cash balance over time (based on 17% mo/mo growth in revenue, and 8.5% mo/mo growth in spending, full model here for you to play with). This is the same company, with the same growth, and the same spend… the only difference here is payment terms:

See the difference? Monthly payments result in bankruptcy (red) and annual payments result in ample and increasing cash (blue). Growth costs money, and if your customers pay annual up front, they pad your cash balance much earlier in their lifecycle.

Even biannual or quarterly payments lead to the same fate as monthly:

The trick here is that if you’re growing quickly (and consistently), then getting paid annually up front funds your growth. This simple change in cash flow is the difference between needing to raise a huge round of financing, and not needing it at all.

From that moment forward, the board made it a policy to only sign enterprise contracts billed annually up front. As a side benefit, this massively simplifies accounts payable for enterprise customers, and simplifies collections for us.

Venture Debt

It seems to be a reasonably common practice to take on venture debt. The idea is to take out a loan from a startup-friendly bank like Silicon Valley Bank, collateralized against the worst case scenario of an acqui-hire or additional VC funding.

A typical venture debt loan in the several-hundred-thousand-to-low-millions is structured something like this:

No payment for 6–12 months, then paid back over the following 2–3 years.

A loan fee: several thousand dollars in cash and a bit less than 1% equity.

An interest rate a couple percent above the federal funds rate.

Required detailed financial reporting on a monthly basis.

There seem to be a couple common use cases for venture debt: delaying fundraising and funding predictable growth. If you’re confident in your ability to raise venture capital down the road, you can use venture debt to get another 6–12 months of growth under your belt and push up your valuation.

Or, if your business is incredibly predictable and you can confidently say that X dollars invested now will generate Y dollars in 12, 24 and 36 months, then venture debt can be an exceptionally cheap way to fund growth. But you’re making a bet that you’ll keep revenue coming in on a steady beat.

When we were considering venture debt vs. Series A in early 2014, we were just barely starting to have our first revenue over the previous 3 months, and new revenue was anything but consistent. The last couple years have also been a great VC fundraising environment with relatively cheap access to capital, so there wasn’t a huge benefit to delaying a fundraising event. In fact, we were excited to have equity investors join the board (Vas at Accel in the Series A and Will Gaybrick now CFO at Stripe in the Series B — both bring huge networks and incredibly valuable perspective in building the business), and the financial reporting requirements for venture debt seemed a bit onerous. We decided to stick with selling equity, and re-evaluate venture debt down the road.

The two scenarios where I’d seriously consider venture debt are: 1. You need a longer bridge between rounds due to lackluster growth. 2. You’re not looking for active investors, and have highly predictable growth.

Shadow Budget

Focus, speed and agility are a startup’s best weapon, so internal bureaucracy is a startup’s worst enemy. Budgets implemented without a clear purpose are definitely unnecessary bureaucracy. So we’ve tried to implement budgets only as-needed, to solve specific problems and eliminate bureaucracy.

As we grew past 30 people we started to notice that team leads were nervous to spend money without some sort of approval, or at least a casual “yep, go for it!” That meant we were moving slower on everyday decisions. Our goal was to enable team leads to spend money as they saw fit, without a complex or unclear approval process. We also wanted a reasonable prediction of how much the company was going to spend over the next 6–12 months.

Initially, we tried implementing full-on budgets as a way to get predictability & enable team leads to spend money. The team leads were responsible for putting their budgets together. Unfortunately, this turned out to be WAY too much overhead, at least for a young team that wasn’t yet familiar with budgeting or balance sheets.

Instead, we ended up settling on what we call a “shadow budget”. Every quarter our CFO uses the past month’s expenses and the team lead’s hiring plan to create a model of how much money we expect them to spend in the next 3–6 months. Then the shadow budget for every team flows up into an overall company shadow budget.

Team leads are not accountable to this budget; it’s just a model that “shadows” reality as best we can. It gives us a guide for comparing what we anticipated vs. reality, quickly revealing any surprises. It’s also a chance to familiarize the team with company financials without burdening them with a full-on budget-planning process. Marketing will be the first part of the org to get a full-on budget, as encouragement to continue growing quickly and also a guideline for spending responsibly.